I criticized the religion of Inbound Marketing in a previous post.

Inbound Marketing: Retards Growth and Turns Marketing Folk into Zombies.

I complained that marketing folk were swallowing the dogma and failing to recognize the practical limitations of inbound (or content) marketing.

But what I didn’t address are two deeper points:

- Inbound vs outbound is a false distinction

- The inbound vs outbound discussion distracts from a couple of more important (but less sexy) considerations

False distinction

Inbound Marketing is based on the idea that it is better for an organization to get its prospective customers to initiate the buying conversation than it is for the organization to initiate it.

So, cold calling is bad. But compelling a prospect to submit a form on a landing page and request content is good.

Well, it’s true that cold calling and driving landing page submissions are quite different activities. But it’s not true that they are fundamentally different. After all, in both cases, the organization is initiating the conversation. In the case of the landing page submission, the organization must have done something to compel the prospect to fill in the form. And that something most likely constitutes an advertisement or a promotional email.

So, at root, all marketing is outbound. In fact, if you have a marketing department that has a policy of not initiating conversations with your marketplace, I think it’s fair to say that you don’t actually have a marketing department!

If we turn our attention back to cold calling vs landing page submissions for a minute, I don’t think it’s even possible to argue that one is fundamentally better than the other. (Bear with me here!).

Cold calling is not 100% evil

Cold calling has a bad rap, undeservedly. If you consider the prospect’s perspective, what’s annoying is not that they have been interrupted—it’s that they’ve been interrupted for no good reason. In other words, their issue is with the content of the call, not with the call itself. After all, if prospects didn’t want to receive calls at all, they could simply disconnect their phones.

The good thing about cold calling is that it scales. I mean, the results don’t diminish with scale. They may not improve much, but they don’t diminish! If you sit down and call a list of 100 prospects, the outcomes from calling the last 10 will be roughly the same as the outcomes from the first batch of 10 calls.

Another plus is that you got to choose exactly who you were going to initiate contact with.

Landing-page submissions are not 100% virtuous

Compare this with landing page submissions. In order to get someone to submit a form on a landing page, you need to attract them to the page in the first place, and then you need to bribe them to submit the form with the offer of something appealing.

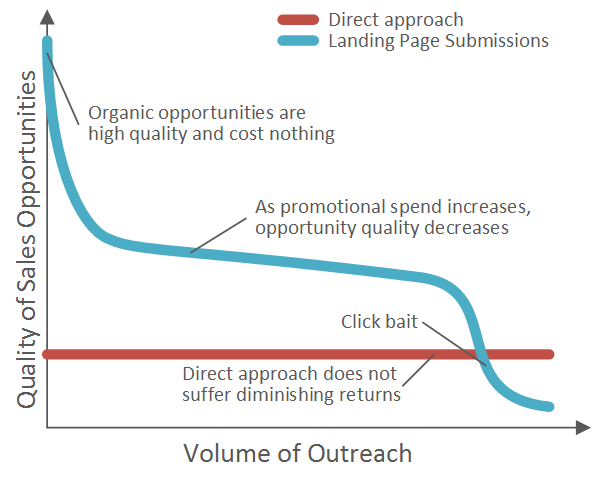

Advertising is expensive. And the more you do it, the more expensive it becomes. Furthermore, market segments get less responsive, the more frequently you put your ads in front of them. So the consequence of increasing cost and decreasing productivity is that you find yourself under enormous pressure to write the kind of hyperbolic ads that drive lots of submissions. (You’ve heard the term click bait, right?).

Here’s a visual representation of what happens.

In summary, inbound and outbound are not fundamentally different. And, at scale, even the quality distinction between cold calling and landing-page submissions becomes questionable.

Two more important (but less sexy) distinctions

Organic vs inorganic sales opportunities

Organic opportunities are the ones you get with no marketing or sales outreach. Existing customers returning to buy again—or referring you to their friends and families. And customers who stumble across you because your product’s the talk of the town (meaning it also ranks at the top of web searches).

These opportunities are free, in the sense that you don’t really need a marketing department to get them. You need a kick-arse product and great execution, of course, but that’s the domain of Operations, not Marketing.

Every business should strive to have such a great product and such good execution that there’s no need for a marketing department—but that’s not the reality for most businesses. Consequently, we do need a marketing department and the job of marketing should be to generate inorganic opportunities (not to falsely claim responsibility for organic ones!).

The inorganic opportunities are the ones you have to invest money (or effort) to generate. On average, their quality tends to be lower than organic opportunities, but they are scalable. There’s a handle you can turn to get more of them.

And turn that handle you must!

Pull vs push

The other important distinction is who is chasing whom? Or, to be more correct, who is chasing whom, at what point in the sales engagement?

By definition, an organic opportunity is an opportunity where the prospect chases your organization from the get-go. They, after all, make the first contact.

Where inorganic opportunities are concerned, your organization is initiating contact. But, at some point during the sales engagement, push has to flip to pull if you want to be able to bank that check.

Of course, the sooner that occurs the better. But if you think about the economics of the sales engagement, there’s a point where you’d really like that flip to occur.

The essential difference between promotions and sales is that, where the former is concerned, marketing folks are communicating with batches of prospects. But, as soon as an opportunity is created and the prospect is handed to a salesperson, the economics change. A salesperson tends to focus on one prospect at a time (and their time is finite and expensive).

What that means is that we’d like the opportunity to flip from push to pull before, or shortly after, the prospect moves from the marketing department to sales.

Before is better. But if it’s to occur shortly thereafter, it must occur on the salesperson’s initial call. That means, when the salesperson calls the prospect, the prospect must welcome the call, even if they didn’t request (or expect) it.

THIS is the critical distinction.

Does the marketing department have a proposition that is compelling enough to flip push to pull before, or shortly after, the salesperson’s initial engagement with the prospect?

With such a proposition, the inbound/outbound distinction becomes academic. Ads become more responsive, landing page submissions more plentiful and cold calls, less cold.

For most organizations, figuring out such a proposition is a really hard problem.

On really hard problems

The first step in solving really hard problems is to recognize that they are, in fact, really hard problems.

The argument that there’s a distinction between inbound and outbound marketing is a great way to sell marketing automation software. But this approach substitutes the really hard problem for a much simpler one, and then offers the tools to resolve the latter!

Most organizations, need to take this problem more seriously. Because of the competitive nature of markets, it’s a problem that’s never really solved. But it’s also a problem where incremental progress can generate out-sized returns.

This post has identified the problem for you (a marketing proposition is required…) and provided an objective means to measure fit-for-purpose (…so compelling that push flips to pull at the salesperson’s initial engagement).

Solving this problem should be an ongoing process that involves senior people from every department of your organization, in perpetuity.