I’m not joking.

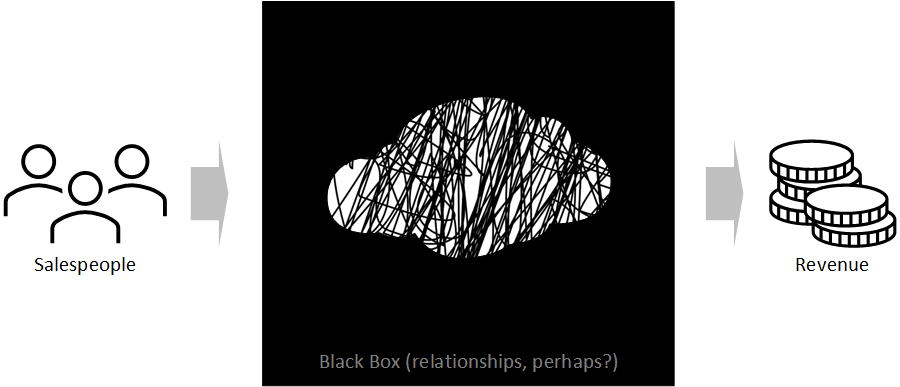

The following is precisely how most executives within industrial organizations conceptualize revenue.

Q. Where does revenue come from?

A. From salespeople.

Q. How do salespeople generate revenue?

A. Um. From relationships.

This conception of revenue is not even vaguely correct. And, unfortunately, this fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of revenue leads to a number of organizational design problems that, collectively, handicap growth.

Cause and effect

Given that revenue is the lifeblood of an organization, it’s probably worth investing a little effort to understand where it comes from.

The proximate cause of a unit of revenue is a transaction. A customer buys something. No surprises here!

Okay, so what causes that transaction?

It’s tempting to answer: a salesperson. But there’s a problem. We know that not all transactions are literally caused by a salesperson. For example, if your salesperson goes fishing for a week, you know that (fortunately) transactions continue in his absence.

Salespeople are happy to furnish a solution to this problem. They will advise us that this magical action at a distance occurs because of the relationships they have developed with their customers.

This explanation is not entirely fanciful (which explains why executives sanction it). I’m reasonably loyal to my hairdresser (hi Brittany!) which, I guess, is evidence of some kind of personal relationship. And I’m pretty sure that you are also somewhat loyal to your hairdresser, your dentist, your gardener, and your personal chef.

But, there’s a couple of problems with this explanation. First, in industrial organizations, most transactions are not accompanied by the delivery of personal services (as is the case with your dentist). Second, in most cases, when a salesperson leaves an industrial organization, their customers stay.

Industrial transactions are programmatic

Another reason why the salesperson’s explanation is somewhat believable is because it is half right.

Transactions do emerge from relationships. But the relationships from which they emerge are commercial relationships, not personal ones.

Unless your organization is operationally dysfunctional, most transactions are programmatic: which is to say that they occur without the provision of personal services. And to the extent that personal services are required, those services are delivered by members of your Operations group (customer service reps, engineers, project managers, etc).

Most transactions consist of existing customers purchasing one more unit of something they have purchased previously. Of course, this state of affairs is something to be celebrated. It’s exactly this phenomenon that drives down unit costs, drives up the profitability of organizations, and enables us all to live our rock-n-roll lifestyles!

Not surprisingly, salespeople are not enthusiastic about the distinction between commercial and personal relationships. It serves them to ignore the qualifier and encourage everyone around them to go on believing that all relationships are of the latter type.

A solution to this semantic problem is to stop using the word relationship altogether. Given that most transactions are programmatic, it’s useful to recognize programs as the source of transactions.

From whence do programs spring?

In industrial environments, programs—rather than discrete transactions—are the default. Imagine you need business cards and your previous provider has gone out of business. When you find a new provider, this print shop gets to print your business cards for you but they also become the default provider of other print services, moving forward. (This is inertia at work.)

If that print shop thinks they are selling you business cards, they are mistaken. They are selling you a program. In financial terms, that program is an annuity, meaning that its value is the net present value of future cashflow.

As is often the case, the value generated by printing a set of business cards is dwarfed by the value of the program, assuming the print shop does a decent job of pricing, printing, and delivering future jobs.

Okay, so where do programs come from? Well, hopefully, your salespeople sell them!

You’ll get some from word of mouth but if you want to grow your organization aggressively, you’ll need your sales team to sell a bunch of programs every month.

If salespeople sell programs, don’t they generate revenue?

If salespeople sell programs and programs generate revenue (via transactions) it would be tempting to conclude that salespeople generate revenue.

But this conclusion is dangerously wrong. It’s a gross oversimplification of the nature of commerce.

From the perspective of Sales, transactions occur on autopilot once a program is sold, assuming that Operations does a good job of onboarding the new customer, and assuming that Operations maintains competitive products, pricing, and delivery performance.

Revenue is actually generated by Operations, not Sales.

Salespeople generate programs. And a program is an annuity: a bundle of potential revenue.

These are NOT the same thing.

How to handicap your organization’s growth

If you fail to recognize this distinction between potential and actual revenue, what you will end up doing is giving your salespeople license to involve themselves in the onboarding and delivery of programs.

There are two obvious problems with this. First, your salespeople are (hopefully) not the best people in your organization to perform operational tasks—meaning your service quality will suffer.

Second, time spent performing customer-service, engineering, and project-management tasks is time that salespeople are not dedicating to the sale of programs.

And if your organization’s going to grow at a faster rate than your competitors, that growth is not going to come from transactions, it’s going to come from the sale of programs.

Justin Roff-Marsh is author of The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function. You can get the first four chapters of The Machine in print or audio version for free here.