Our first order of business is to address two questions that have the potential to derail this discussion.

The issue is not that these questions expose weaknesses in Sales Process Engineering (SPE). The issue is that these questions stand in the way of our discussion even getting started!

Considering the radical nature of the change we’re contemplating, it’s only natural to ask:

- If the standard sales model is so dysfunctional – and if there’s a better method available – why haven’t more companies adopted it already?

- If the standard model has evolved over many years – and withstood the test of time – how can it be that this model is fundamentally flawed?

Why do we persist?

There are two (interrelated) reasons why we persist with the traditional approach to the design of the sales function.

First, the standard model conforms with all our assumptions about how sales should be made. And, second, it is impossible to inch your way to the new model – a revolution is required.

Deeply-held assumptions

If we are to evaluate the standard model with reference to long- and deeply-held assumptions about how to generate sales then the standard approach to the design of the sales function measures up well.

Ask yourself, do you agree with the following statements:

- Sales of expensive products and services are highly dependent upon personal relationships

- A successful sales function is highly dependent upon star performers

- Salespeople should be encouraged to operate autonomously – to view their territory almost as if it is their own business

- Customers require – and benefit from – a single point of contact with their suppliers

- Sales improvement is all about improving conversion (plugging the leaky funnel)

Each of these statements sounds innocent enough, right? But, for most salespeople – and their managers – these statements are more than true. They are axioms (fundamental, self-evident and unquestionable truths). Attempts to challenge them will be met with injured feelings, or even hostility.

Consequently, any approach to sales improvement that is in alignment with these axioms will feel right. But an approach that conflicts with one or more will almost certainly be dismissed out of hand. As you’ll discover in due course, SPE conflicts with every one of these axioms – and with numerous other commonly-held beliefs about sales too.

Sadly, the serious consideration of SPE tends to require at least one of the following conditions:

- The performance of the sales function must be so bad as to shake management’s faith in the standard model to its very core

- A senior executive with no prior exposure to sales (perhaps an engineering or production specialist) must turn their attention to the sales function

Almost without exception, our silent revolutionaries began their investigation of SPE only when both of these conditions were in place!

Incremental change won’t cut it

The other hurdle to the adoption of SPE is the magnitude of change required for the successful transition.

Consider just a few of the changes that have to occur:

- Salespeople must willingly give-up ownership of their calendars and ownership of sales opportunities

- Salespeople must be prepared to spend all of their time in the field (in practice this means a five- to ten-times increase in territory size: and, consequently, a lot more travel)

- Management must be prepared to add new team members and – possibly – to see some existing team members exit the organization

- Management must be prepared to assume (and, ultimately, reassign) responsibility for the origination of sales opportunities

And then there’s the impact on the rest of the organization:

- In many cases, customer service needs to be reengineered to cope with the additional load

- The new project leadership function must be tightly integrated with production and customer service

- If production scheduling has devolved into brinkmanship to accommodate the demands of a small number of increasingly-powerful customers, this negative trend must be reversed

When you consider the counter-intuitive nature of SPE and the significance of the transition from the standard model, it’s little wonder that the standard model persists.

But it can only persist so long!

There’s a slow trickle of sales managers (and even salespeople) who are recognizing the dysfunction within their sales functions. And there are numerous executives from other functions who are growing restless with the under-performance of sales and who are starting to suspect that the emperor has no clothes!

How did we get here?

The standard sales model didn’t used to be dysfunctional.

For much of the history of industry, this model has been the optimal one. (In fact, there are situations today, where the standard model is still quite appropriate.) What has happened is that industry itself has undergone two sea-changes and sales has stayed pretty much the same.

From production- to sales-focused

In the 1989 classic, Field of Dreams, Kevin Costner’s character plows under his corn and builds a baseball field in the hope that if he builds it, he will come. Fortunately ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson and his colleagues arrive just in time to rescue the hapless farmer from bankruptcy.

Today, the phase build it and they’ll come is often used to reference the unrealistic expectation that production is sufficient to create a market. However, for most of the history of industry, production has, in fact, been sufficient.

Until recently, the salesperson’s job was to take a highly differentiated product and demonstrate it to potential customers. Sure, there was a requirement for some salesmanship but, for the most part, the sale was really made in production.

Today, because the market is so much more competitive, it’s unusual for a product to be highly differentiated. It’s common for customers to choose product a over product b and reasonably expect to pay a similar price for a product that performs almost identically. It’s true that we still have true ground-breaking products, but these are much more likely to be the exception, rather than the rule.

Because production has been the primary success driver for most of our recent history, this is where our capital and our brainpower have been invested. And the return on this investment has been staggering. Over the last 100 years we’ve seen orders of magnitude increases in productivity (measured against any reasonable standard) and orders of magnitude improvement in quality.

We’ve seen at least three major revolutions in production. Frederick Winslow Taylor introduced scientific management at the start of the last century. Ford’s approach to mass production drove costs down to unprecedented levels. And, in the 1950’s W. Edwards Deming jump-started the quality movement, contributing to the rise of Japan and subsequently revolutionizing operating procedures in production facilities the world over.

Of course, the rate of change we’ve seen in production cannot be sustained forever. Increasingly, managers are recognizing that their advances in production have exposed sales (including distribution) as the weak link.

Today, sales is the new frontier. We’re already seeing the focus of senior management shift to sales (and with focus comes capital and brainpower). My prediction is that the next 50 years will bring revolutions in sales similar in scope and consequence to those we’ve seen in production.

Let this book be the first shot across the bow of the good ship Orthodoxy!

From make-to-stock to engineer-to-order

As mentioned previously, the fundamental assumption that sits at the base of the standard sales model is that: sales is the sole responsibility of an autonomous agent.

If we consider how a typical organization has been structured for most of the history of industry, this assumption is a perfectly reasonable one.

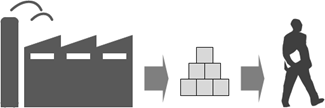

Make-to-stock

Above is a traditional value-chain. The production facility produces to maintain a stockpile of inventory. The salesperson sells from this inventory.

In this environment, it makes perfect sense for the salesperson to operate autonomously. The firm as a whole benefits when its salespeople sell as much as possible. Because inventory is already sitting in a stockpile, orders can be fulfilled as soon as they are received. And because of this stockpile, there is minimal requirement for interaction between sales and production.

Increasingly, this is not how value-chains are configured. We have seen a recent and dramatic shift from make-to-stock to make-to-order environments. The latter reduces holdings costs and provides customers with greater choice. In a make-to-order environment it no longer makes sense for the salesperson to simply sell as much as possible. The salesperson needs to sell only what production has the capacity to produce. Rather than operating autonomously, the salesperson must subordinate to production.

This is complicated by a further twist in the value chain. Today, an increasing number of products (as well as almost all services) are actually designed (engineered) as they are being sold. In an engineer-to-order environment, tight integration between sales, engineering and production is critical. The degree of integration determines both the likelihood of the sale being won and the quality of the product delivered.

In such an environment, sales cannot possibly be the sole responsibility of an autonomous agent. In fact, for this reason, the standard model damages both sales performance and product quality (and, therefore, customer satisfaction).

In summary, the standard model always has and perhaps always will make sense in make-to-stock environments – where it is possible for the sales function to operate at arms-length from production. Such environments include:

- Most consumer goods (typically sold in retail environments)

- Consumer and small-business financial services (insurance and investment products)

- Packaged software

However, in make-to-order and (particularly) engineer-to-order environments, the requirement for tight integration between sales, engineering and production renders the standard model dangerously inappropriate. Environments like:

- Business services (consulting, legal and finance)

- Design-and construct building

- Enterprise software

Now we understand why sales environments look the way they do today – and why change is not necessarily an appealing proposition – let’s return to the task at hand: redesigning the sales function.

Direction of the solution

Let’s consider how we might go about causing a dramatic increase in the productivity of the sales function. What might be the direction of the solution?

We should immediately discount traditional sales-improvement initiatives (sales training, for example). History suggests that, at best, such initiatives produce only incremental results.

For inspiration, we might look to manufacturing. This makes sense because we know that this is one part of the organization that has seen a dramatic increase in productivity in recent times.

Do we know the cause of this dramatic change? As it happens, we do.

In 1776, in his magnum opus, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith predicted that division of labor would drive a massive increase in productivity. He told the story of a pin-manufacturing operation where 10 workers had divided the production procedure into 18 distinct steps and shared these steps among themselves.

Individually, each worker could produce 20 pins a day. Collectively they were producing 48,000!

The benefits of division of labor are not enjoyed only in manufacturing environments. If we take a stroll around a typical organization, we discover division of labor in all types of production environments, in engineering and even in finance. In fact, the only part of the organization that has not embraced division of labor is sales!

Assuming that there is no reason to immediately disqualify division of labor, let’s assume that this is the direction of our solution.

Playing the Devil’s advocate

But, not so fast!

If we were to commission an experienced salesperson to defend the standard model – to be the devil’s advocate, as it were – can we imagine their objections to the concept of division-of-labor?

These are likely to be their two primary objections:

- Complexity: “Sales is complex in most environments nowadays. You have multiple influencers and decision-makers. You have numerous conversations with multiple parties spanning weeks or months. This complexity does not lend itself to division of labor.”

- Personal relationships: “People buy from people. No one likes to transact with a machine. Division of labor will destroy the critical personal relationship between the salesperson and the customer.”

Before we directly address these objections, it’s interesting to observe that these are similar in nature to the objections you might hear from a craftsperson (an artisan) who is being encouraged to transition to a modern manufacturing environment.

This person is likely to suggest that if they do not personally craft their product, any increases in efficiency will surely be offset by a reduction in quality.

Of course, history suggests that the artisan’s concerns are unwarranted! It just so happens that the changes we must make to a production process to improve efficiency are the very same changes that are required to maximize quality. (The quality revolution taught us that the words efficiency and quality are functionally synonymous.)

Complexity

Our devil’s advocate is correct. A modern sales environment is certainly likely to be complex – for all the reasons stated.

But is complexity a reason to avoid division of labor?

If it is, we should see a decline in division of labor as we examine environments of increasing complexity. Let’s consider two extremes in a production context: the assembly of a hang-glider, versus the assembly of a jet aircraft. The notion of a single person assembling even the simplest of jet aircraft is laughable. The fact is, in truly complex environments, division of labor is not just possible: it’s essential.

Our devil’s advocate has identified a potential problem in the application of division of labor – one we’ll grapple with in due course – but they have not dealt our proposed solution a lethal blow.

Personal relationships

It’s true that people enjoy (for the most part) interacting with other people. It’s also true that many salespeople have good relationships with accounts.

However, it’s dangerous to assume (as salespeople frequently infer) that these relationships cause sales.

To see why, we should enquire into the origin of a salesperson’s relationships. Specifically, which comes first, the sale or the relationship? The reality is, for the most part, the salesperson’s relationships are the consequence of sales, not their first cause!

Now, our devil’s advocate is unlikely to take this line of reasoning lying down! His immediate objection will surely be that the distinction between first and proximate cause is purely academic – and that if relationships and sales are related, it matters little how they came to be that way!

It’s here that we must make a critical distinction – a distinction between the initial transaction in a series of transactions and the rest of those transactions. In most cases, the salesperson’s initial transaction signals the acquisition of a new account. All of the subsequent transactions (assuming the same product or service type) are repeat purchases. The first transaction – because it signals the acquisition of an annuity – is many times more valuable than each of the subsequent ones.

Because initial and subsequent transactions are materially different, it doesn’t make sense to lump them together and refer to them all as sales, as our devil’s advocate is doing.

So, for the balance of this book, we will use the word sale to refer only to the acquisition of a new account (or the sale of a new product or service line to an existing one). We will refer to repeat transactions as transactions.

We must consider, now, the contribution that the salesperson’s relationship makes to the retention of existing accounts. There’s no question that this relationship must factor into the retention equation but, what are the other considerations?

As we’ll discuss in much more detail, every organization must have three core functions to be viable in the long run:

- New-product development

- Sales

- Production

It’s revealing to rank these three functions in the order in which we believe they will impact account retention.

In spite of the fact that salespeople, all over the world, are allocated responsibility for retention, it is extraordinarily rare to find a salesperson who will identify sales as the primary influencer of retention! Almost, without exception, salespeople recognize that production performance is the primary. In other words, the number-one thing that an organization must do to retain its customers is deliver on time, in full, without transactional errors.

Salespeople will also willingly volunteer that the number-two thing that an organization must do is ensure that its products are consistently better than – and cheaper than – its competitors’: which is, of course, the responsibility of new-product development.

The shocking reality is that salespeople contribute little to retention, relative to production and new-product development – in spite of the fact that it is their responsibility (consider how many salespeople are actually referred to as account managers)!

If you are deficient in the areas of production or new-product development, it may be that your salespeople’s personal relationships cause accounts to persist with your organization a little longer than they otherwise would. However, to claim that personal relationships cause sales amounts to either equivocation or outright denial (or a little of each!)

Putting division of labor to work: four key principles

With those objections out of the way, we’ve bought ourselves a little bit of time to piece-together our solution. Division of labor is not the solution, after all – just the direction of the solution.

Our devil’s advocate intuitively recognized this when they raised the objection about complexity.

The thing is, when we apply division of labor to any environment, things tend to get a lot worse before they get better! The rewards offered by the successful transaction from the craftshop to division of labor are exciting (as reported by Adam Smith all those years ago) but the transition itself is difficult and extraordinarily perilous.

The fact that production has been the primary focus of industry for the last 100 years is evidence of the difficulty of the transition. The good news is that, if we intend to lead our sales function down the path already taken by production, this is indeed a well-trodden path.

The lessons from manufacturing can be generalized into four fundamental principles:

- Centralize scheduling

- Standardize workflows

- Specialize resources

- Formalize management

We’ll dedicate the balance of this chapter to the exploration of these principles – in their natural manufacturing context. And, in the next chapter we’ll figure-out how to repurpose these principles for the sales environment. First, however, we need to be sure we understand the nature of the problem we are attempting to solve. To achieve that, we’ll turn our attention to a boat race.

The primary challenge

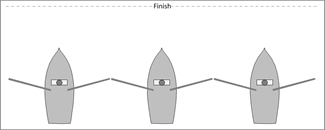

Two boat races, in fact: both time trials. In each case the oarsmen will attempt to maximize the speed of their vessels.

Autonomous agents

In the first race, each oarsman commandeers his own boat. Each is an autonomous agent. When the starter’s gun fires, each oarsman must do his level best to maximize the speed of his vessel. And he does that, not surprisingly, by rowing as fast as is humanly possible.

This race is an allegory for the craftshop environment in manufacturing (and for the standard sales model).

Division of labor

In the second race, we make one subtle change. We put all the oarsmen in the one boat. The goal is the same: maximize the speed of the vessel. But each of the oarsmen must undergo a radical shift in his approach to the goal. If each oarsman rows as fast as is humanly possible, the speed of the vessel will definitely not be maximized.

If each oarsman maximizes his individual rate of work, the consequences will be a lot of noise, clashing of oars and, possibly, a capsized boat! In this second race (an example, of course, of division of labor) the speed of the vessel is determined primarily by the synchronization of the oarsmen – not by their rates of work.

Now, the shift of focus from individual effort to synchronization may not seem significant but it is – particularly when we consider environments more complex than a row boat. Learning to row in unison with others is tricky, but this skill (in this context) is made easier by two factors:

- You are operating in close proximity to your colleagues – you simply stroke in time with the oarsman ahead of you

- You have immediate feedback – you can see and feel the impact of your actions on the performance of the vessel as a whole

These factors tend not to be present in a more typical work environment (few people, today, work in row boats).

In a reasonable-sized manufacturing plant, for example, it’s unlikely that all of the workers contributing to a process are in visual contact with one another. And, in a knowledge-work environment like (say) a sales function, work-in-progress is invisible and lead-times are long – meaning that there is no immediate feedback.

In such an environment, how do workers synchronize their rates of work? The short answer is that, without special intervention, they simply don’t.

Here’s an interesting thought experiment.

Consider the changes we would need to make to our row-boat model in order for this model to be representative of a standard work environment (production or sales).

How about we replace each of the oarsmen with a rowing machine – a powerful solenoid, operated by remote control? And, how about we put each of our oarsmen in a cubicle in an office complex – with a remote control unit?

On each remote control unit is a button that actuates the solenoid back in the boat and causes that oarsman’s two oars to stroke. If each oarsman is isolated from the boat – and from his colleagues – and he is committed to winning that race – how will he determine when to press the button?

Sadly, this humorous scenario is not dissimilar to many modern work environments. To complete the picture, all we need to do is add a manager who attempts to improve the performance of the boat by running from cubical to cubical encouraging everyone to row harder – and then who periodically berates team members for their lack of communication!

Principle 1: centralize scheduling

To claim that division of labor causes workers to become disconnected from the performance of their overall system is stating the obvious. After all, as we’ll soon discuss, a narrowing of the worker’s focus is both a benefit of, and a necessary condition for, division of labor.

It’s inevitable, then, that division of labor will result in synchronization problems.

The solution is to centralize scheduling.

If you think of any work that you perform, that work can be broken into two components:

- The critical activities that cause matter (or information) to change form

- The determination of the sequence in which to perform these tasks and of when, exactly, to commence each

The second component of work is what we’ll be referring to as scheduling.

Of course, scheduling is pretty easy when it’s just you doing the work. You can learn the basics in a half-day time-management workshop! However, as you add more workers to the work environment, scheduling rapidly becomes very difficult.

The key to avoid synchronization problems when we apply division of labor is to first split the responsibility for these two types of work. If we fail to do this, the local efficiency improvements that result from workers focusing on a single task will quickly be eaten-up by the general chaos that spreads through the environment (remember the clashing oars in the row boat).

There are many environments where the centralization of scheduling is a well-established practice:

- The manufacturing plant (where scheduling is the responsibility of the master scheduler)

- The project environment (where the project manager owns the schedule)

- The orchestra (in a string quartet, the first violin sets the tempo; however, in the case of a full orchestra, a dedicated conductor is required)

- The airport (consider the chaos if, in the absence of an air-traffic controller, pilots had to decide among themselves when to take-off and land!)

In each of these cases, scheduling is a specialty. (The project manager doesn’t wear a tool belt and few air-traffic controllers even know how to fly planes.)

Now, it’s true that even the most complex sales environments are less complex than a busy airport but, it’s also true that almost every sales environment is significantly more complex than a row boat. Therefore, if we are entertaining the idea of applying division of labor to sales, we must first acknowledge that the very first activity for which the salesperson relinquishes responsibility will be scheduling.

Post script

Until now, we have accepted that, in a simple environment – like a row boat – division of labor doesn’t require the centralization of scheduling.

However, it’s interesting to consider what we might do if we were really serious about winning the boat race we discussed earlier.

If you look at most competitive rowing teams you’ll discover – you guessed it – centralized scheduling!

Centralized scheduling

In a scull, for example, the coxswain sits in the stern of the boat, facing the oarsmen, and sets the tempo to which the oarsmen row.

If we consider the racing scull for a moment, we can draw two interesting observations that relate to scheduling in all environments:

- The coxswain is a dead weight (he does not row) and his inclusion increases the weight of the vessel by a significant amount. It’s reasonable to assume, then, that the performance improvement resulting from the inclusion of the coxswain more than compensates for this weight increase. And this is in an environment where the centralization of scheduling is not even critical!

- The coxswain maximizes the speed of the boat by causing all of the oarsmen to row at the same speed as the slowest oarsman. Therefore, to maximize the speed of the boat, all but one of the oarsmen must row slower than they possibly can.

Principle 2: Standardize workflows

The need to standardize all workflows is regarded as self-evident by many managers. Note the attention paid to standard operating procedures in a modern workplace.

But it’s worth acknowledging that standardization is only a necessity in an environment where division of labor has been applied.

If we were to insist that an experienced craftsperson create (say) violins following exactly the same sequence of steps for each instrument, it’s not so clear that craftsperson’s productivity would increase.

Consider sales environments, for example. Almost every mid- to large-sized firm has invested tens (or, more commonly, hundreds) of thousands of dollars in CRM technology in recent years on the promise of increased sales performance. If you examine business cases for typical CRM implementations, you’ll discover that many of these promises hinge on an assumption that the standardization of salespeople’s procedures will cause an increase in sales.

Of course, it’s rare to encounter an organization that can point to any performance improvement that is attributable to the CRM. The reason for this is simple: capable salespeople neither need nor benefit from the standardization of their operating procedures. In fact, the CRM has provided capable salespeople with additional overhead: data-entry that must be done purely to satisfy management! When you consider the small number of sales opportunities that a typical salesperson is prosecuting at any point in time, it’s clear that the salesperson’s trusty Franklin Planner is significantly more useful than the CRM!

But division of labor changes things: standardization suddenly becomes critical.

When the person who plans the work (the scheduler) is remote from the people who do the work, the standardization of procedures (and workflows) prevents the complexity of environments from multiplying to unmanageable levels.

In manufacturing environments the workflow is referred to as the routing. The routing is the path that work will follow through the plant, taking into account both the activities that will be performed and the resources that will perform them. The general rule in manufacturing is: same product, same routing.

If we apply division-of-labor to the sales environment, we must standardize our workflows for the same reason. For this environment to be manageable and scalable, all opportunities of the same type (same objective) must be prosecuted using the same routing – from the origination of opportunities, through their management.

Principle 3: Specialize resources

In discussing the centralization of scheduling we’ve already broached the subject of specialization. We know that when we apply division of labor, the scheduler is the very first specialist.

Indeed, once we have centralized scheduling and standardized workflows, specialization is relatively easy.

Specialization causes a significant increase in workers’ productivity for two reasons:

- When a worker performs activities of just one type, they become very good at performing those activities

- Switching between materially-different activities imposes a significant overhead on a worker. The elimination of this switching (multitasking) increases that workers effective capacity

Of course, specialization doesn’t just relate to people. In most environments, today, activities will be shared between people and machines (including computers). However, we should note that automation has not been the root cause of productivity improvement in the last 100 years. The primary is division of labor. After all, it’s division of labor that has allowed us to simplify activities to the point where they can be performed by machines.

Principle 4: Formalize management

It’s interesting to note that there’s no essential difference between a scheduler and a manager.

To appreciate why, let’s consider when and why the concept of manager sprung into existence (at least in a business context).

In the craftshop environment, there was no such thing as a manager. Division of labor created a requirement for managers because, as workers became specialists, someone had to synchronize the operation of the work environment as a whole. That’s right; manager is just another word for scheduler!

Today, scheduling is still management’s primary responsibility; it’s just that modern managers employ technical types to do the more detailed scheduling, freeing them to focus on compliance and the synchronization of their function with the rest of the organization.

Although scheduling and management are essentially the same, in practice, the manager plays a critical role for two reasons:

- Division of labor causes work environments to become inherently fragile

- Because the organization consists of a number of functions – each of which could be characterized as an oarsman in a larger boat – someone must pay attention to the synchronization of the organization as a whole

Specialization is a two-edged sword. It causes a dramatic increase in the productivity of each individual but it also causes each worker to operate in a vacuum – intently focused on their own work in progress (or their task list). To a great extent, the scheduler compensates for this narrow focus, but the manager is still required to ensure compliance with the schedule, to resolve problems as they occur and to make decisions relating to the design and resourcing of the overall environment.

If we consider that the organization as a whole consists of a number of functions (sales, engineering, production, finance, etc) then we can see that the synchronization of the firm is as necessary as the internal synchronization of each function. This is the responsibility of the management structure as a whole, including all executives from the CEO down. In short, it’s the responsibility of each functional manager to ensure that their function makes the necessary contribution to the goal of the organization (we’ll pay more attention to this subject in due course).

You may be wondering why this principle is entitled formalize management, as opposed to just manage. Well, in the context of this book, the distinction is important. A sales manager in a traditional sales environment is not a manager and nor can they be.

Management only becomes possible after the application of division of labor. If the essential responsibility of management is scheduling – and if the salesperson in the standard model operates autonomously (they own their own schedule) – then a sales manager in this environment is a manager in name only.

By the way, the common claim that I manage outcomes is not a defense; it’s an admission of liability. To manage outcomes is to not manage at all. A manager who manages outcomes is a spectator, not a manager!

So, armed with the direction of our solution (division of labor) and the four key principles that enable division of labor to work in practice, let’s turn the page and envision a brand new model for the sales function.