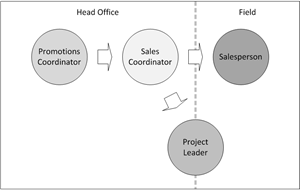

We commence with the direction of the solution (division of labor) and four key principles. On an otherwise blank sheet of paper, we have a single salesperson.

Yesterday, our sales function essentially consisted of a single salesperson. Tomorrow, sales will be the responsibility of a tightly synchronized team.

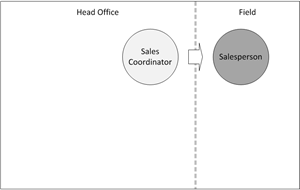

Principle 1: centralize scheduling

Our first principle dictates that, as we push towards division of labor, our very first specialist must be a scheduler.

We’ll elect to call our scheduler a sales coordinator.

It’s important to note that this person is not a sales assistant. The word assistant would imply that it’s the salesperson who allocates work. The opposite – as indicated by the direction of the arrow – is the case. The sales coordinator allocates work to the salesperson.

This means that the salesperson must transfer any and all scheduling responsibilities to the sales coordinator. This may be a more significant undertaking than it sounds when you consider that, in most cases, the salesperson’s scheduling responsibilities are not limited to the management of their own calendar. In most cases, salespeople are interfacing with production and customer service, coordinating the delivery of their clients’ jobs.

At this point in the discussion it’s premature to allocate specific activities to resources but it will do no harm to draw four very general conclusions:

- Our sales coordinator must perform all scheduling

- Our salesperson will spend more time selling

- Our salesperson should work in the field (not in an office)

- Our sales coordinator should work from the head office

The first two conclusions are not at all contentious. But the second two are less obvious, but important, none the less.

Salespeople work in the field: not an office

Traditionally, salespeople split their time between the field and an office. And this is unavoidable when you consider the diverse range of activities for which salespeople are responsible.

If we have a choice, however (and we soon will), it makes sense to have salespeople spend all of their time in the field, for two reasons:

- If we are going to spend the (not insignificant) money required to employ field salespeople, it makes sense to have them selling in the field where, presumably, they’re more effective

- A fundamentally different approach is required for scheduling field- and office-based activities – meaning that it’s impractical to schedule a blend of both

Where the second point is concerned, field activities tend to be allocated to specific time slots – and protected with significant time buffers. (Prospective clients would rather salespeople’s visits are pre-booked – and have little tolerance for salespeople who fail to appear when scheduled). This is not the case with office tasks. In most cases it makes much more sense to allocate activities to a list – and then sort that list dynamically to ensure that activities are completed within an acceptable lead-time. (In the first case, the worker goes to the work, in the second the work comes to the worker.)

When salespeople visit the office, they inevitably bring their field practices with them – meaning that they are shockingly inefficient, compared to a dedicated office-based person. Of course, this sets a poor example for their office-based colleagues.

The sales coordinator works from head office

It would be tempting to assume that the sales coordinator should operate in close proximity to the salesperson – but the opposite is true. The sales coordinator should operate in close proximity to the business functions with which sales must integrate.

We’ve already discussed that the integration between sales, engineering and production is becoming increasingly important for the modern organization. Well, it just so happens that integration is significantly easier to achieve if the individuals responsible for scheduling each function operate in close proximity to one another.

Additionally, if you consider the salesperson’s perspective, the salesperson will feel less disconnected from the organization as a whole if their sales coordinator is operating from head office.

The relationship between the sales coordinator and the salesperson

Although we are (for simplicity) drawing our inspiration from manufacturing, there is another type of production environment that is a better analogy for the sales function). It’s the project environment. Certainly, it’s healthy (particularly in major-sales environments) to recognize that sales opportunities are projects – and then to manage them as such.

We’ll expand on this idea shortly, but for the meantime, let’s consider the relationship between the sales coordinator and the salesperson by contrasting sales with another project environment where we have senior people working closely with schedulers.

That environment is the executive suite. In the executive suite of a decent-sized firm we will likely encounter at least one executive who works closely with an executive assistant. Unlike a plain-vanilla assistant, an executive assistant assumes overall responsibility for the initiatives (projects) in which the executive is involved – and, also, assumes responsibility for the executive’s calendar.

The executive assistant maintains an awareness of all the initiatives upon which the executive is working (and their relative importance) and plans the executive’s time so as to maximize the yield on their limited capacity.

If we take the preceding sentence and substitute executive assistant for sales coordinator and executive for salesperson, then we have a perfect functional description of the role of the sales coordinator. And if we reflect on the nature of the relationship between the executive assistant and the executive, then we will observe exactly the relationship that must exist between the sales coordinator and the salesperson in order for the sales function to be productive.

This discussion also sheds light on the inevitable questions about whether, in practice:

- Salespeople will find it demeaning for someone else to plan their calendars

- Potential customers will find it disturbing if salespeople fail to set their own appointments

The answer to both questions is a firm no. Treating salespeople like executives does not demean salespeople and, if anything, it elevates their standing in the eyes of potential customers.

Principle 2: standardize workflows

We’ll return to the subject of resourcing (and our diagram) in a moment. First we must standardize our sales-related workflows.

Our second principle dictates that we use a standard sequence of activities to:

- Originate opportunities (identify or generate sales opportunities)

- Manage opportunities (prosecute opportunities – resulting in either a win or a loss)

It makes sense to treat these as two workflows (rather than one) because opportunities tend to be originated in batches but prosecuted one at a time. Because opportunities tend to be originated in batches (via either prospecting or promotional activities) the idea of standardizing the first workflow is not a foreign one.

However, the case for standardization is not so clear when opportunity management is concerned. It’s easy to see that standardization will yield internal efficiencies, but we must explore whether or not our ability to win orders will be negatively impacted by standardization.

Or, to frame this consideration as a question: do our salespeople require unlimited degrees of freedom in order to effectively win orders?

The case for standardization

To address this question, we should first acknowledge that, whenever we are selling, a potential customer is buying. Therefore, our opportunity-management workflow is the flip-side of our potential customer’s procurement workflow.

So, we can reframe our question: do our customers require unlimited degrees of freedom in order to make an effective purchasing decision?

Viewed from this perspective, the answer is, not necessarily. Increasingly, organizations are standardizing their procurement procedures for those products or services they purchase regularly. What’s more, different organization’s procurement procedures, for similar products, tend to be remarkably similar.

If we consider major purchases, I suspect the greater variation we see in procurement procedures is more a consequence of an absence of procedure than it is evidence of the absence of a need for one. In other words, I’m suggesting there probably is an objective ideal procedure for making major purchases – it’s just that, because organizations make major purchases infrequently, they haven’t gotten around to figuring out what it is!

I’ve often asked groups of salespeople who sell major products (enterprise software, for example) if there’s a right and a wrong way for organizations to purchase a product like theirs and I’ve always been impressed by how well-reasoned and unanimous salespeople’s responses are.

My suggestion, then, is that there is an ideal opportunity-management workflow for both minor and major purchases. Where minor purchases are concerned, this is more likely to be determined, in advance, by your customers but there’s unlikely to be enormous variation, from customer to customer. Where major purchases are concerned, customers are unlikely to be aware of the ideal procurement procedure, presenting you with an opportunity to take the lead and help them discover it.

If you sell major products (where major refers to the magnitude of the decision, not the dollar value), your entire opportunity-management workflow should be designed around the concept of you taking the lead – but we’ll return to this point in a moment.

The anatomy of an opportunity-management workflow

Your opportunity-management workflow is little more than a sequence of standard activities. Here’s a typical sequence for a minor product (or service):

| # | Activity name | Description | Objective |

| 1 | Capability-showcase meeting | Present organization’s credentials and demonstrate capability | Gain agreement for requirement-discovery meeting |

| 2 | Requirement-discovery meeting | Determine client requirements and direction of solution | Gain permission to present proposal in formal proposal-customization meeting |

| 3 | Proposal generation | Generate proposal | |

| 4 | Proposal-customization meeting | Present proposal and fine-tune options relating to features, pricing, etc | Gain order for product or service |

If we think of a sales opportunity as a project, then the table above is our project plan. In other words, it’s our sales coordinator’s job to schedule each of these activities in the sequence specified with each potential customer. And, as indicated by the objective column above, it’s our salesperson’s job to sell the next significant activity at each meeting.

At the first meeting in the sequence, the salesperson should sell the workflow as a whole. Now, because opportunity-management workflow is not a particularly client-friendly term, it’s more likely that the salesperson will present this critical sequence of activities as your engagement model. (From now on, we’ll use these terms interchangeably.)

Major product sales

Where major-product sales are concerned, it’s necessary to make one fundamental change to the design of the opportunity-management workflow.

As hinted a moment ago, the absence of a formal procurement procedure provides an opportunity for your organization to take a leadership position. Specifically, if your potential client is not practiced in purchasing whatever it is that you’re selling, then you should take the opportunity to manage their procurement procedure for them.

You do this by breaking your opportunity-management workflow into two parts:

- Sell a solution-design workshop, feasibility study or similar

- Via the solution-design workshop, sell your ultimate product or service

The solution-design workshop is a structured procurement procedure – facilitated by you, on behalf of your potential client. In many cases the solution-design workshop will be more than a single workshop: it’ll be a sequence of activities, like the following:

- Pre-workshop research

- Solution-design workshop (attended by all decision makers and key influencers)

- Preparation of outcomes document (often a PowerPoint presentation)

- Formal presentation of findings meeting (attended by all decision makers)

More often than not, it will be possible to charge for a solution-design workshop – and if you can, you should! But regardless of whether or not you charge, your solution-design workshop must be structured so that it delivers true stand-alone value to your potential client. (In other words, it cannot be a thinly-veiled sales presentation.)

When you are delivering a solution-design workshop, you have an obvious conflict of interest. This means that you must to go to special trouble to ensure that your methodology is robust and your reasoning, immaculate.

Principle 3: specialize resources

If we return to our project analogy for a moment, we now have a project plan (our opportunity-management workflow), a project manager (our sales coordinator) and a resource pool containing a single resource (our salesperson).

It’s time now to add to our resource pool so that we can exploit some of the potential of division of labor.

A nice starting point is to consider all of the activities performed by a typical salesperson and determine which can be allocated to other resources.

| Activity name | Resource (current) | Activity type (proposed) |

| Prospecting | Salesperson | Promotion |

| Appointment setting calls | Salesperson | Administrative |

| Calendaring and travel arrangements | Salesperson | Administrative |

| Sales meetings | Salesperson | Sales |

| Follow-up calls | Salesperson | Administrative |

| Solution design | Salesperson | Technical |

| Proposal generation | Salesperson | Semi-technical |

| Production-related activities | Salesperson | Technical |

| Post-sale customer service | Salesperson | Semi-technical |

| Processing (repeat) transactions | Salesperson | Semi-technical |

| Data entry and reporting | Salesperson | Administrative |

Beside each activity above is a proposed activity type. Some of these are obvious – and some are a little contentious. So, let’s be sure to resolve the contention, if we can, before we re-allocate four of the five following activity types:

- Promotion

- Administrative

- Sales

- Technical

- Semi-technical

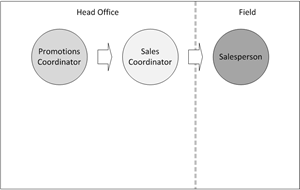

Promotion

It is possible for salespeople to generate their own sales opportunities but, the fact that they can does not constitute an argument that they should (and this statement applies to almost every other activity above too). The thing is, the generation of sales opportunities is extremely resource intensive if they are originated one at a time – and salespeople lack the resources required to generate them in batches. Typically the batch-generation of sales opportunities requires the ability to procure and manipulate contact lists, the ability to produce funky promotional campaigns, the resources to broadcast personalized e-mail (or snail mail) and perhaps even the ability to promote and coordinate events.

Salespeople lack these capabilities, so it makes sense to allocate responsibility for prospecting to the marketing department – and for marketing types, the generation of opportunities belongs to a subset of marketing called promotion.

But before we hand over prospecting to the marketing department, we need to be very clear on two points:

- The person responsible for opportunity generation must be part of the sales function (not the marketing department)

- A sales opportunity is only an opportunity if the potential customer has already been sold an initial meeting with the salesperson

If your firm is big enough to have a marketing department, it’s big enough for people in that department to be pulled in all directions at once! Because your sales function can’t operate without sales opportunities – and because sales is a critical function – there’s a pretty sound argument that the generation of sales opportunities should take automatic priority over any other demands on marketing people’s time. But, in reality, that will never happen!

The solution is to add a promotions coordinator to the sales function and make this person responsible for the administration of all promotional activities and, therefore, for the generation of sales opportunities. Your promotions coordinator should then use the marketing department as a resource for the creation or promotional collateral and so on.

If yours is a small firm (with no marketing department), point one is no big deal. If you need to add a promotions person, simply add a promotions coordinator to the sales function and have them outsource work that would otherwise have been performed by the marketing department.

Now, where point-two is concerned, if your promotions coordinator is responsible for the generation of sales opportunities, we need a functional definition of sales opportunity. You should define a sales opportunity as: a prospect who has requested a meeting with a salesperson or who is likely to accept one if offered.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the responsibility for selling the salesperson’s initial meeting with a potential customer must rest firmly on the promotional coordinator’s shoulders (and not the sales coordinator’s).

Administrative

It should be easy to see why data entry, reporting, calendar management and travel arrangements have been categorized as administrative activities but, what about appointment-setting and follow-up calls? How can they possibly be administrative?

Let’s start with follow-up calls.

As we have discussed already, at each meeting within the opportunity-management workflow, it’s the salesperson’s job to sell the next critical activity. If the next activity has already been sold, the scheduling of that activity is purely an administrative function. The standardization of the opportunity-management workflow has automatically eliminated the requirement for salespeople to make unplanned and unstructured telephone calls.

Now, it is true that prospective customers will often need to be called multiple times before a meeting is finally scheduled, but hustling ain’t selling: it’s hustling – and good administrative people make much better hustlers than salespeople!

On the occasion that an administrative person discovers that further input from the salesperson is required before the next activity in the workflow can be scheduled; the administrative person should either schedule another meeting with the salesperson, or a teleconference. In either case, this additional meeting does not constitute a material change to the opportunity-management workflow; it’s just a repeat of the preceding activity.

If you think about it, the initial appointment-setting call is no different from follow-up calls. If (and only if) the meeting has already been sold, the call is simply a scheduling exercise.

Here’s a real-world example:

Nigel is the director of sales for a large recruitment firm (one of our silent revolutionaries). Because he also happens to be most capable public speaker in the sales department, he’s now addressing a room full of senior executives – introducing a controversial approach to headcount management.

At the close of his presentation, he will ask delegates to complete a feedback form and encourage them to tick a box at the bottom of the form to indicate that they would like to schedule a best-practice briefing with Rick, the firm’s local consultant (salesperson).

It’s Nigel’s expectation that a little more than 20% of delegates will tick that box and virtually all of them will meet with Rick. What’s interesting is that Rick’s sales coordinator is unlikely to call any of them. Setting those appointments is such a simple undertaking that she will simply send each an e-mail, asking them to nominate their preference from a number of available meeting slots.

This is an example of an effective promotions campaign: evidence that, if promotions is done properly, even the initial appointment-setting call is purely administrative in nature.

In due course, we will pay much more attention to promotions. I understand that the generation of opportunities is a tough problem for many organizations – and that my new definition of opportunity makes this problem even more onerous – but, for the moment, I have to ask you to suspend your disbelief!

As perhaps you’ve already guessed, all administrative tasks (including both initial appointment-setting and follow-up calls) will become the responsibility of the sales coordinator.

Technical

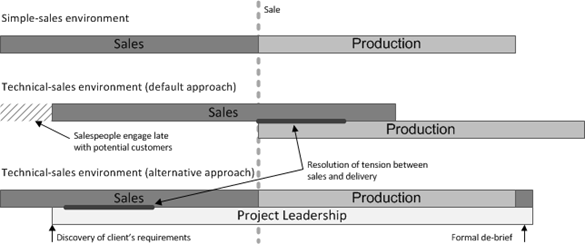

Every major-sales environment has the same problem.

Salespeople become entangled in the delivery of the solutions they sell – and this entanglement cannibalizes their selling capacity.

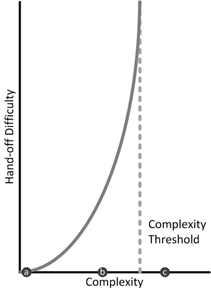

This inevitable entanglement has a simple cause. The thing is, above a certain level of product complexity, a perfect hand-off from sales to production is impossible. Not just difficult: impossible. This means that, beyond this complexity threshold, information will always be lost when sales hands-off the project to production. This information-loss cannot be eliminated with more detailed briefings, more documentation or management exhortations to better communicate.

This graphical depiction of the complexity threshold shows that hand-off difficulty goes to infinity when

complexity increases beyond a certain point. The markers on the x-axis suggest the degree of complexity in

three environments: (a) make to stock; (b) make to order; (c) engineer to order

There are only two possible solutions to this problem:

- Propose only products that are simple enough to sit beneath the complexity threshold (limit customization to a fixed menu of options)

- Eliminate the requirement for a hand-off altogether

Of course, in major-sales environments, the second option tends to be the default approach. What happens is that the salesperson never fully hands-off to production: they remain on-call, post-sale, to answer questions and to interface with the client.

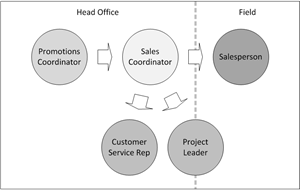

There is, however, another approach: one that has a profound impact on both sales effectiveness and service quality. The alternative approach is to add a third party to the mix: a person we’ll call a project leader.

In a major-sales environment there are two approaches to the avoidance of hand-offs.

In the default approach, the salesperson remains engaged through delivery.

This results in a reduction in the salesperson’s selling capacity and, consequently,

late engagement with potential clients. It also defers resolution of the inevitable tension

between sales and production until after the sale is won.

In this alternative approach, the project leader and the salesperson work side-by-side for most of the opportunity-management workflow.

Here are the essential characteristics of this approach:

- Because the salesperson has no post-sale responsibilities they have more selling capacity. This enables them to engage earlier with clients than they otherwise would – meaning that initial contacts are conceptual in nature.

- At the point at which the client wishes to discuss (in concrete terms) their requirements, the salesperson introduces the project leader.

- The project leader takes responsibility for requirement discovery and for solution design (in many cases, these will occur in the form of a formal solution-design workshop).

- From this point until the point of sale, the salesperson and the project leader work together. The project leader is responsible for the technical component of the engagement and the salesperson, the commercial component.

- Post sale, the project leader champions the project as it moves through production. This means that the project leader replaces the salesperson as the primary point of contact for both production and the client.

The sole responsibility of the project leader is to manage the interface between production and both the client and sales. When they do their job well:

- The product presented to the client is both saleable and deliverable (taking into account features, price, delivery lead-time, etc)

- The product that is ultimately delivered to the client fulfills the client’s requirements, without compromising the profitability of the organization (understanding that the client’s requirements may well have changed – or been reinterpreted – during delivery)

Because the project leader seeks to optimize the numerous trade-offs though both the opportunity-management and delivery phases of the engagement, it should be clear that their role is critical and their contribution invaluable. For this reason, the project leader should always have protective capacity (they should never be over burdened with work). Accordingly, it is not a problem that the project leader works both in the office and in the field. If we are deliberately maintaining the project leader at less than 100% utilization, it is obviously not necessary to maximize their efficiency.

Semi-technical

Semi-technical activities include the generation of standard proposals, the processing of repeat transactions and the provision of after-sales support.

All these activities – as well as any others that are semi-technical in nature should be allocated to the customer service team.

Curiously, most organizations already have customer service teams. However, the primary responsibility for customer service rests with the salesperson. The result tends to be that the customer service representatives are disillusioned and generally unprepared to take ownership of customer service cases (we’ll use the word case to refer to a unit of customer-service work).

This means that two changes must occur. The customer service team must rapidly develop both the capability and the capacity to take full ownership of the entire customer-service case-load. And, salespeople must extricate themselves from customer service.

In practice, the latter is not as difficult as it sounds. With two simple initiatives, it can be accomplished quite quickly:

- Salespeople must avoid taking ownership of customer-service cases in the first instance. This is easier than it sounds. For example, if a client asks a question about an incorrect order, the salesperson might use their cell phone to initiate a three-way conference call between the client, a customer-service representative (CSR) and themselves.

- Customer service representatives must assume ownership of cases as soon as they encounter them. With this in mind, it is useful, in the design of your customer-service workflow, to stipulate that the CSR must send the client an e-mail when each case is opened and closed. Obviously, the first e-mail should make it clear that the CSR is the person responsible for resolving the issue and is, consequently, the primary point of contact.

The customer-service team must be head-office based (close to production). If there’s a requirement to perform field visits in order to resolve customer-service cases (perhaps to inspect a problematic product), the CSR should task the project leader to perform this visit and report back with the necessary information.

If we return to our project analogy – where we compare a sales coordinator with a project manager – we can now see that our sales coordinator has inherited a resource pool consisting of three resources (salesperson, project leader and customer service representative).

This means that, in order to prosecute each sales opportunity, the sales coordinator will break the opportunity into a series of activities and allocate each activity to one or more of these resources, in accordance with the routing specified in the opportunity-management workflow.

The client’s perspective

It’s easy to see that this model is quite ordered and logical from the organization’s perspective: but what about the client? In asking our clients to interface with multiple people, haven’t we just made their worlds more complex?

It’s true that in this model, clients will interface with four people (sales coordinator, salesperson, project leader and customer-service representative).

It’s also true that, today, most clients ask for – and most organization’s strive to provide – a single point of contact. However, reality is a little more complicated than this.

It’s a mistake to commence this discussion with an assumption that the traditional model delivers good customer service. It simply doesn’t.

It’s also a mistake to take clients’ claim that they’d rather have a single point of contact at face value. In practice, clients can be quite aggressive in seeking-out relationships with other individuals if they sense this is in their best interest.

My experience is that the following statements are closer to the truth (particularly in major-sales environments):

- Clients don’t mind multiple points of contact, but they want a single conversation. In other words, they will willingly speak with multiple people within your firm as long as they do not have to repeat themselves.

- If clients have a choice between dealing with a single generalist and multiple specialists, they would rather speak with specialists.

- Although we talk about the client as if this were a single entity, in most cases, there are multiple people client-side involved in the purchase and consumption of your products.

You will discover that this new model provides a vastly better quality of service, provided you ensure that:

- There is a clear delineation of the responsibilities of the four parties with whom clients interact

- Sales coordinators (who are planning all opportunity-management activities) and CSR’s are in close communication with one another

Principle 4: formalize management

As discussed, the downside of division of labor is that it causes environments to become fragile. Although it’s the responsibility of the sales coordinator to synchronize the various team members, management oversight is critical for a number of reasons:

- Sales coordinators tend to be younger and less-experienced than both salespeople and project leaders. Accordingly, the sales coordinator’s mandate is very limited. If the sales environment is operating exactly as it should be, they have total control over the schedule. However, a relatively small disturbance in the operation of the environment can render them impotent.

- The sales function must integrate effectively with other functions (production and marketing, to name two). Because the sales coordinator tends to be relatively inward-looking, it’s necessary for a more senior person to interface with those other departments.

- In most sales environments there are multiple sales coordinators (one for each salesperson). This means that a more senior person must manage any contention between sales coordinators (or salespeople).

- As with any environment, there’s a requirement for a senior person who is somewhat detached from the day-to-day minutiae, to perform a periodic audit

Hence the requirement for a sales manager.

The sales manager’s most important duty is to chair a regular (at least weekly) sales meeting. To be effective the sales meeting must have an explicit agenda, it must run to the agenda, and it must be short (20 minutes)!

The model for an effective sales meeting should be the standard factory (stand-up) work-in-progress meeting.

The enduring challenge with sales management in general, and with the conduct of sales meetings in particular, is the absence of objective information. Many organizations have given up on sales meetings because, in the absence of objective information, they are ineffective, at best; caustic, at worst.

With division of labor, an interesting change has occurred, with respect to management information. Previously, all sales-related information was owned by the salesperson – who was free to reveal (or not) this information when it was advantageous to them.

In the new model, the sales coordinator is the central information repository. Not only are they aware of sales activities before the salesperson (they schedule them), but they receive accurate and timely updates from the salesperson (the salesperson can only disadvantage themselves by failing to communicate).

Provided, then, we have the necessary technology (a subject we’ll get to in due course), we are now in a position to have an objective – and therefore productive – sales meeting.

In addition to the conduct of sales meetings, the sales manager should be responsible for:

- Accompanying salespeople in the field to share best practice between salespeople

- Accompanying salespeople on (typically) late-stage meetings to assist in the winning of deals

- Participating (along with other senior managers) in the formulation of offers and other decisions that must be made by a multi-functional committee

- Whatever activities are required to maintain the overall health of the sales environment and the quality of the interface between sales and other functions

It should go without saying that this new model empowers the sales manager. With the critical combination of information and control (via the sales coordinator) they are transformed from a lobbyist to a true manager.

* * * *

In chapter one, we encountered James Sanders Group (one of our quiet revolutionaries). We discussed Jennifer’s enormous productivity and the productive relationship she has with David (her sales coordinator) and Phillip (a project leader). We also discussed the critical role that customer service has played in the remarkable transition that has occurred at JSG.

This chapter should have shown how our four key principles lead logically to this end result. In part two of this book we’ll pick up on the many threads left open in this chapter. We’ll talk more about major-account selling, about promotions, technology, and so much more.

But before, we dive deeper into the practical workings of SPE; we should widen our focus and consider the sales function as a single cog within a much larger machine or, if you like, as the machine within the machine.